Seattle, We Have a Base Ball Team! The Seattle Alkis and the Arrival of Competitive Base Ball in 1877

100 years before the Mariners played their first season, the Alkis gave Seattle fans their first taste of the base ball epidemic.

It’s been a minute, but I am back! Before we go back in time 150 years or so, I went back to 1996 and 2001 with the To Love a Mariner podcast. We watched the home videos issued after those seasons, You Gotta Love These Guys and Sweet 116, and discussed them thoroughly. It was really fun to record and I think you’ll have a great time listening! You can find it wherever you get your podcasts.

Now, to the 19th century we go!

Baseball took its time arriving in Seattle. Most corners of Cascadia saw base ball match play before the Emerald City. It was played in Victoria, British Columbia as early as 1863 and the first competitive base ball club was established in Oregon in 1866.

Teams proliferated in Oregon’s Willamette Valley and across the river in Vancouver, Washington Territory in the 1860s. Walla Walla, once the most populous city in the territory, organized its first base ball club in 1867. The first teams in Idaho sprouted in 1868 and Olympia formed a number of teams beginning the same year.

Of course, Seattle wasn’t the largest city in the territory when clubs began forming; it was barely more than a village. As the population grew, so did the appetite for social clubs and recreation. In 1870, the population of Seattle surpassed 1,000 for the first time, and base ball appeared.

The Dolly Varden Base Ball Club

The first known base ball club in Seattle named itself the Dolly Varden Base Ball Club. They were welcomed to life by an item in the Puget Sound Dispatch on July 11, 1872 announcing the formation of the club and listing the officers.[1]

If you have any familiarity with 19th century base ball nationally, the Dolly Varden name stands out. It was used by a number of teams, perhaps most famously by the first known Black women’s team that played in Philadelphia in 1883.[2] The name was taken from the flashy, colorfully attired character in Charles Dickens’ 1841 novel, Barnaby Ridge. Dolly Varden dresses and hats became popular in the 1870s along with namesake base ball clubs.

The president of the Seattle Dolly Vardens was William G. Jamieson. He moved to Seattle from Victoria, where he served as secretary and played for the Olympic Base Ball Club in 1869. Jamieson came to Seattle in September 1870 and opened a jewelry business on the corner of Commercial and Mill Streets. His stay in Seattle was brief—by 1880 he had moved on to Walla Walla—but his base ball club organizational know-how was invaluable in Seattle, from the Dolly Vardens to the Alkis.

The Washington Standard in Olympia wrote it was “rumored that the Seattle Base Ball Club intends to challenge the Washington Club, of this place, to play a match game.” There is no evidence that a challenge was issued or that the match—or any other match—took place.[3]

The history of early baseball leans on match games. We love the spirit of competition and match games drew more coverage in newspapers. But base ball clubs didn’t always play match games. They typically had plenty of members to field at least two full teams, and most often played amongst themselves.

In 1887, Edward R. Brown, the secretary of the Dolly Vardens, wrote to the Seattle Post-Intelligencer from his new home in Sitka, Alaska with a full roll of membership.[4] This suggests the club did play games and was significant enough to warrant a mention in the newspapers in later years when Seattle’s baseball scene was more established.

The Skooknni Base Ball Club

The Dolly Vardens appear to have lasted only one year. In April 1873 a new club was organized in Seattle, the Skooknni Base Ball Club.[5] Many of the same people on the Dolly Varden membership roll were also members of the new club, including Brown. The item announcing their formation in the Puget Sound Dispatch called for anyone “desirous of joining the club” to contact Secretary Brown.[6]

I could find no further mention of the Skooknnis in the newspapers, nor of base ball in Seattle for the next few years. That's understandable for the village was busy growing into a city.

Railroads and Coal and Growth

The 1870s were a decade of tremendous growth in the northwest, particularly in the Puget Sound region. In the early part of the decade, Tacoma and Seattle, along with Olympia and Steilacoom, were in a heated battled to win the Northern Pacific Railroad’s western terminus. Tacoma won, and was on a path to become the northwest’s largest, premier city.

It was a blow to Seattle to lose out to Tacoma, but the city saw no reason to douse its delusions of grandeur (a founder did try to name it New York, after all) and remained steadfastly committed to the belief that the city would fulfill the wildest dreams of its capitalist inhabitants.

Most of the country was suffering through the first Great Depression (it was renamed the Long Depression when a Greater Depression came along), that lasted from 1873 to roughly 1879. Despite the “hard times and general business dejection” that “hung like a pall over the great commercial marts and cities of the Union at the East,” the Post-Intelligencer wrote on January 1, 1877, “At no period in the history of our pioneer city has its growth been so rapid as during the twelve months just closed."[7]

Buildings were erected, industries sprouted and grew, and the population increased. Growth required energy, and luckily Seattle had a local source right across the lake, as long as it could find a way to transport it.

In January 1864, a surveying party sent out on behalf of King County’s Government Land Office discovered coal on the north bank of a creek that would be creatively named Coal Creek on Cougar Mountain (the discovery site is near the current-day Red Town Trailhead).[8] Land was claimed and small-scale mining began almost immediately, however, the mine owners ran into the same problems that had bedeviled earlier mining attempts in nearby Renton and Issaquah. The coal was located in dense forests with thick underbrush and swampy land. It wasn’t as easy as loading up a wagon and hauling it where it needed to go.

The coal was too valuable to leave undisturbed on the mountainside. The area was named Newcastle after the famous coal city in England, and numerous groups of investors formed over the years to solve the transportation problems. A railroad was attempted, but ran into financial difficulty and was abandoned. A wagon road, that ran down the hill to Lake Washington, followed. From the lake, the coal was pulled on barges and down the Black and Duwamish Rivers to Elliott Bay. The round trip took 5 days [9] and couldn’t possibly move enough coal to make the mines financially feasible. Investors in 1871, hoping to open more markets and spur yet more investment, sent coal to San Francisco, the 10th largest city in the country and with no coal source of its own. It became a lucrative market and transportation investment continued in Seattle and the coal-rich area to the east.

In 1872 Seattle had its first locomotive. Named the Ant, it was able to pull 8 coal cars, dramatically increasing the amount of coal that could be transported in one go. The area’s connection with Seattle also strengthened in 1872 when a steamer began offering passenger service from Yesler’s Wharf (the present-day ferry landings on the Seattle waterfront) to Murphy’s Landing (south of what is now Pleasure Point in Renton, north of the VMAC. Go ‘Hawks).

By 1874, a new railroad built by the Seattle & Walla Walla Railroad & Transportation Co ran from the Newcastle bunkers to Lake Washington. In 1876, the railroad was expanded to run around the lake all the way into Seattle. The ease of transportation meant mining was finally becoming lucrative. The area, including Newcastle, Renton, and Talbot, supplied nearly 20% of San Francisco’s coal, not to mention quenching Seattle’s need for energy.[10]

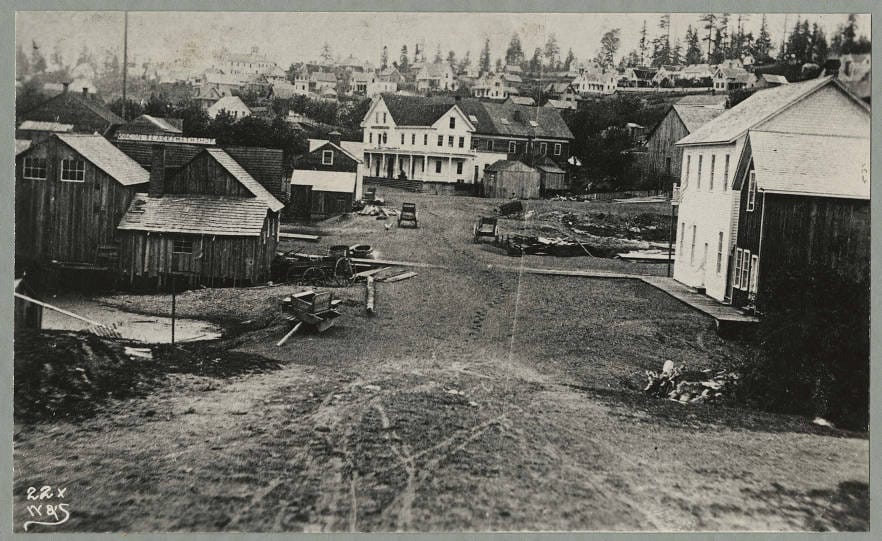

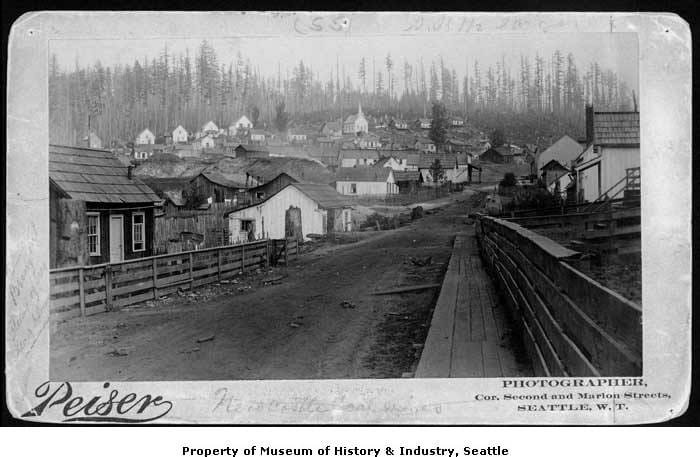

In 1876, Newcastle had a general store, post office, justice court, and at least two saloons, and a reporter from the Post-Intelligencer, on a trip to visit the mines, noticed there was “less drunkenness than could possibly have been expected in a coal mining town.” The reporter noted the town had “over one hundred buildings and seventy families." [11] To give you an idea of the growth the town experienced, by 1878 the Post-Intelligencer estimated the town had 250 or 300 families.[12]

The First Company Teams

In later years, amateur and semi-pro baseball leagues would thrive in the mining areas of Washington state, with rival mines and company towns competing for bragging rights. 1876 saw the first of these match games. On June 24, 1876 a match was held “in the vicinity of Newcastle.” A full score wasn’t given, just the note that “The Newcastle miners won the game, beating their Renton friends 12 points." [13]

On August 20th, the teams had a return match, hosted by the Renton club. At 9 AM, “the Renton Club, Renton Brass Band and large delegation of gentlemen and some of Renton’s “fairest daughters”” were at the landing (it’s unclear which landing, or where the game took place) when a steamer that transported the Newcastle club, along with a fifty or sixty member entourage of both gentlemen and ladies, pulled up to the dock. The Newcastle club, it was noted several times, were wearing red caps, and as the band played “several neat and appropriate airs”, the Newcastle delegation cheered back, “Three times, three and a tiger!" [14]

From the dock, the the teams proceeded to the ball ground:

The game was hotly contested on both sides, but it soon became evident that the “red caps” were a little too much for the Renton boys. Nine innings were played and the Newcastle boys were declared the victors, with 42 runs against Renton’s 25.[15]

Following the game, the Newcastle Club was treated to a reception and dinner at the home of George W. Tibbetts. Tibbetts was instrumental in building the city that would become Issaquah. A native of Maine who moved west after serving in the Civil War, he settled in the Squak Valley in the early 1870s after he and his wife left a homestead in Oregon. Tibbetts became a territorial legislator, helping draft and pass the bill that built the Snoqualmie Pass highway and clearing a way over the Cascades for the first time. In 1888, he built and operated the Bellevue Hotel, which was a popular stopping point for voyagers through the mountains. Tibbetts also played a role in spurring violence against Chinese laborers in the Squak Valley in 1885,[16] a precursor to larger, more violent events elsewhere in the region.

But, he was a prominent member of society on the Eastside at the time, and therefore was naturally involved with the formal base ball clubs. At his home following the game, the members of each club “did justice to an ample repast of all the delicacies of the season.”

After winning two match games, the Newcastles were ready for a new challenge.

The Seattle Base Ball Club

Sometime in 1876 or early 1877, Samuel L. Crawford arrived in Seattle to work for the Post-Intelligencer. He learned the newspaper trade and the base ball game in Olympia and brought his expertise in both north.

It was said that Sam spent his evenings in Occidental Square (roughly the site of Occidental Park in Pioneer Square now) “tossing the ball around”.[17] He drew like-minded fellows to join him, including James Warren, Jack Levy, and Jack Wilson. Players would later offer conflicting stories about exactly how the team was formed; most said either Crawford or Levy saw a notice in the Post-Intelligencer from the Newcastle Base Ball Club offering to play any club in King County and the guys decided to form an official club and accept the challenge.

However, it seems more likely that the club was formed first. On March 21, 1877 the Post-Intelligencer, likely Crawford himself, wrote that a new base ball club was in the process of being organized and the “proposed members have been practicing for sometime." [18] The newspaper suggested once the organization was “perfected” they would send a challenge to the Renton club.

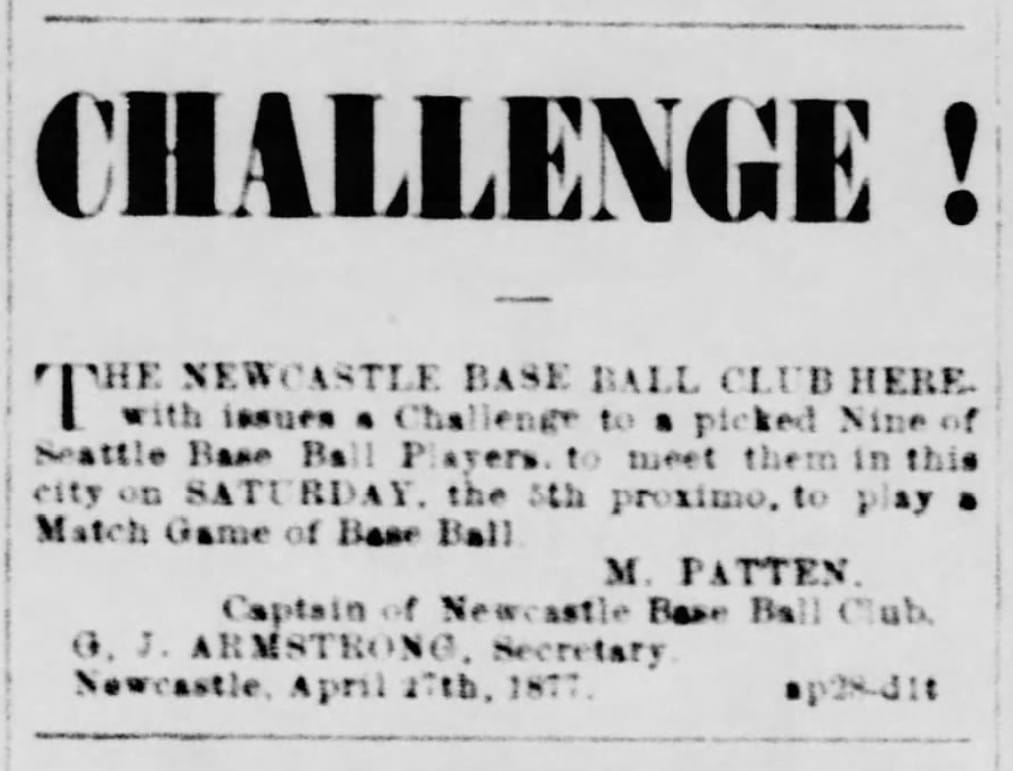

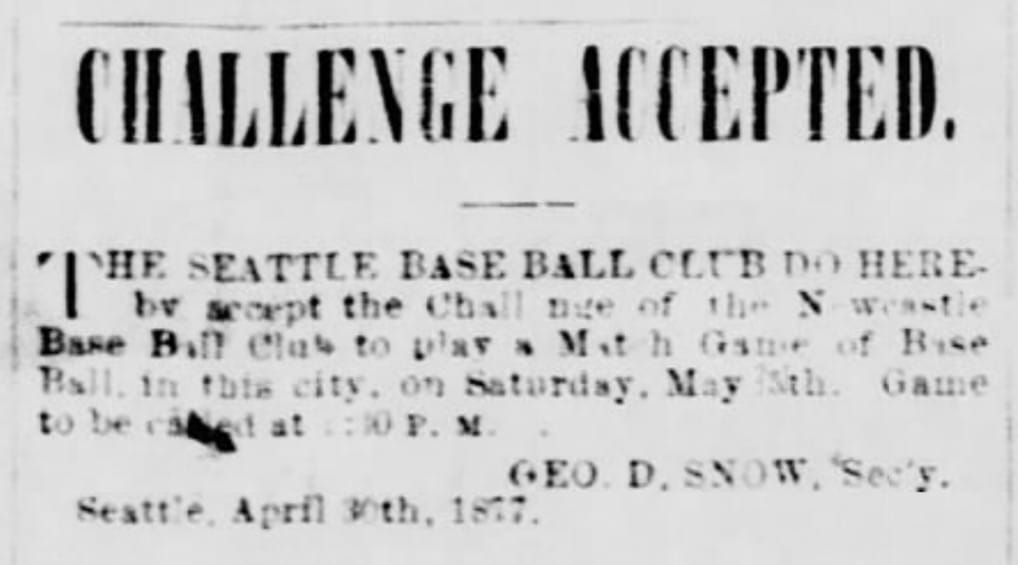

The Newcastle Base Ball Club beat Renton once again and snagged the first game honors. At the end of April, M. Patten and G. J. Armstrong, Captain and Secretary respectively of the Newcastle club sent a challenge via the Post-Intelligencer to play a game in Seattle on May 5th.[19] A few days later George D. Snow, Secretary of the-then nickname-less Seattle Base Ball Club wrote back to accept the challenge.[20]

The acceptance was followed by a flurry of excitement as the city prepared to host its first game. The Post-Intelligencer wrote a couple days before the match that “interest in it is kindling up perceptibly.” It was expected the Newcastle team would travel to Seattle with a large delegation and that spectators would travel to Seattle from elsewhere on the Sound to witness the occasion. “A gala time is anticipated by all." [21] It was appropriate that the first match game in Seattle was with Newcastle, considering how inextricably entwined each town's growth and evolution was with the other.

The game was held on the grounds of the Territorial University of Washington (Go Dawgs). The university opened in 1861 and initially educated children of all ages. It wasn’t until 1876 that the first collegiate degree was awarded, a Bachelor of Science to Clara A. McCarty. The Territorial University was located at present-day 4th Avenue and University, the site of the current Fairmont Olympic Hotel (and, I must note, a full university degree’s tuition in the 19th century cost less than staying at this hotel for one night costs now).

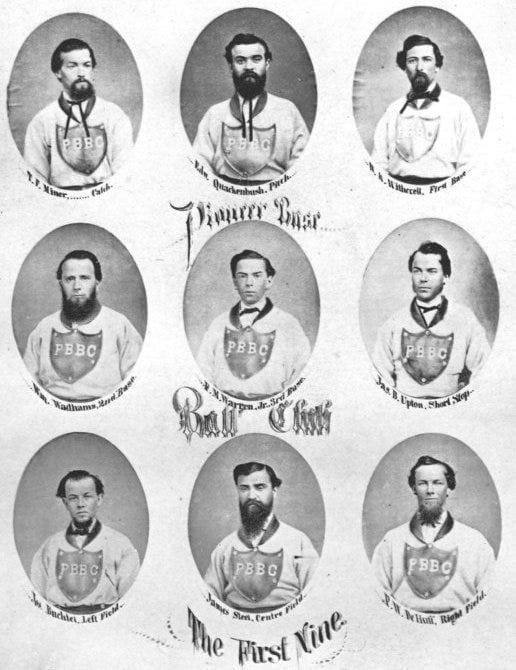

The Newcastle club arrived in Seattle on May 5th with “a neat appearance in their new uniforms,” and a nickname, the Lone Stars. They appeared to be formidable opponents. “Their quick and sure handling of the ball gave rise to the opinion that “Our Boys” would have an uphill road to travel,” wrote the Post Intelligencer [22] of Newcastle club’s pre-game warm up. In contrast, the Seattle club had no uniforms and wore their regular daily attire on the field.

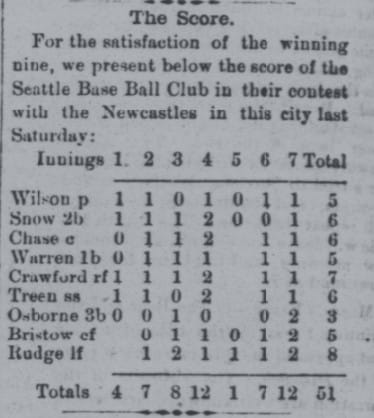

The game began at 2 o’clock, with Seattle’s pitcher, Jack Wilson, reaching on a leadoff hit. Follow up hits by George Snow, Curry Chase, and James Warren contributed to the 5 runs Seattle scored to begin the game.[23]

In the bottom of the 1st inning, the leadoff hitter for Newcastle drove the ball to right field, where it was easily fielded by Crawford. Wilson was quick to establish himself as the first ace in Seattle base ball history. “The accuracy and effect of his pitching is shown by the fact that Wilson had only 3 balls called on him during the whole game, while only 3 Newcastle men reached first base." [24]

Despite the worries that Newcastle would prove a tough opponent, Seattle had no trouble putting away their opponents from Cougar Mountain. When the dust settled, after 7 innings of play, the score was 51-0.

In later years, the Seattle players would claim that the game was stopped in the 7th inning “by the Newcastle boys throwing down their clubs and quitting, a most disgusted lot!" [25] Although I found no evidence of that in the contemporary newspapers articles about the game, I did note that there was no description of a social gathering following the game, as was customary at the time. Still, it feels as though if the mores of Victorian-era society had been disrupted like that, the newspapers would have made a snide reference.

The Post Intelligencer lamented the blowout victory. A “tremendous throng of spectators was in attendance, and at times the most intense excitement prevailed, although the game was hardly close enough to awake the interest it otherwise would have done had it been closer." [26]

If only Seattle base ball fans had known to relish the dominance, for it would be the exception, rather than the rule, in the century and beyond to come.

The Seattles Become the Alkis

Not long after their first match game, the Seattle Base Ball Club received a challenge from the Victoria Nine in British Columbia, picking up the tradition that Victoria and Olympia base ball clubs had of trading match games on Queen Victoria’s birthday and Independence Day. The challenge was accepted and the intrepid Seattle club headed north for the match on May 24th.

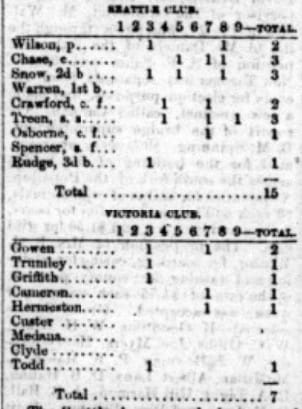

The Victorians fielded a picked nine of four different clubs in the area. It seemed at first glance that it would be a tough game for the new Seattle club. But once again, first impressions were deceiving. The Victorians struck first, scoring 4 runs in the 3rd inning, but were only able to cross the plate 3 more times. Seattle answered in the bottom of the 3rd with 3 runs, and continued to score while showing “their opponents some new things in pitching and catching, fielding and hitting that would have been creditable in professionals." [27] Seattle won again, 15-7.

Even after the loss, the Victorian showed them a good time. The clubs went to the Gorge to watch boat racing and “were treated to a banquet such as has seldom been equaled and never excelled on the Pacific Coast." [28]

Opening a season with 2 wins is sure to strike joy and optimism in the heart of any baseball fan, and the fans in Seattle were deliriously happy about the play of their new team. Businessmen in Seattle took up a subscription to give the team “a rousing salute on their return." [29] When the team’s steamer pulled in to Seattle from Victoria, they received a 21-gun salute, a band played in celebration, and a large crowd greeted them at the docks.[30]

The newspapers of the day may have trafficked in hyperbole, but the pride in the accomplishments of the new nine were clear when the Post-Intelligencer wrote “The boys have done nobly, and reflected credit on themselves and the city." [31]

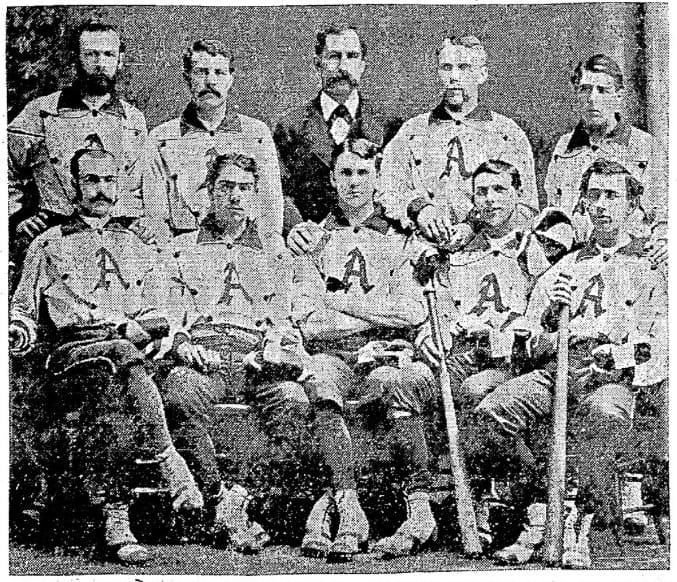

Upon returning, and in preparation for the Fourth of July rematch, the club held a meeting and got serious. They decided upon a uniform: “Dark blue pants, white shirts, trimmed with blue, white and blue striped stockings, and blue caps." [32] They adopted a new name and became the Alki Base Ball Club.[33]

"Alki" comes from the Chinook jargon term for "soon" or "in a little while" or "by and by". When the first settlers in Seattle landed at what is now Alki Point, Lee Terry thought it resembled Manhattan Island and decided to name it New York (he later returned to New York and stayed there). Legend says that new arrivals would look at the island named New York and say, "Yeah, maybe a long time from now." Eventually it took on Chinook jargon word and became known, more appropriately, as Alki.

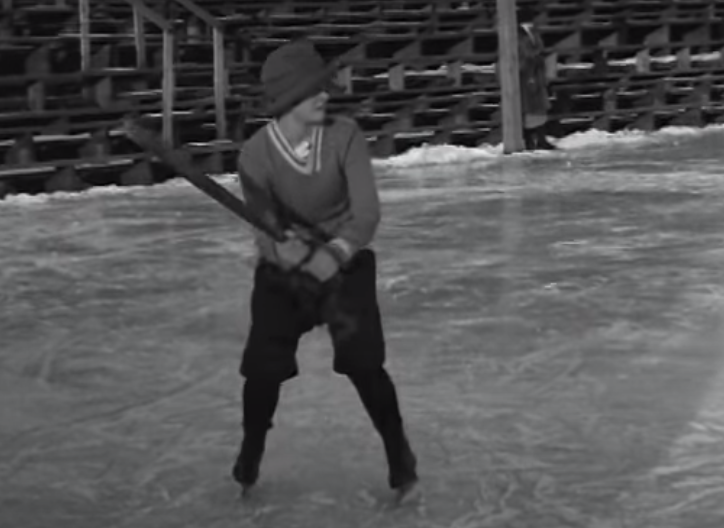

The new Alkis also established playing grounds near the horse racing track in present-day Georgetown. Because the regrading of the city’s hills had not yet begun, there were few cleared, flat-ish pieces of land on which to play. Thanks to the interest in building railroads, the players were able to take a train from the city center south to the racetrack grounds.

The return match with Victoria began at 11 o’clock in the morning at the racetrack. The Post Intelligencer wrote that “there were upwards of 1,000 people on the ground all anxious to see the game commence." [34] This was remarkable if at all accurate considering the city’s population was about 3,000 at the time (some of the crowd would have been part of the entourage to travel south with the Victorians). The Alkis dealt with injuries to their catcher, Chase, who cut his hand the day before the game on an exploding soda bottle at Levy’s Soda Works, owned by the family of Alkis president, Jack Levy.[35] During the game, Crawford suffered a sprained ankle. (The Intelligencer initially reported that their employee muffed a fly due to the injury; the next day a correction was issued that he did not in fact make a mistake in the field. He simply could not run the bases.)[36]

The offense in the game took a while to warm up; neither team scored in the first 5 innings. But the bats heated up and “in the latter half they were sent through with telling effect." [37] Despite his injury, Chase scored the most runs. The Alkis were once again victorious and the final score was 21-9.

The Bach House

In between matches, this delightful item ran in the Weekly Pacific Tribune:

Some eight young gentlemen, all members of the Alki Base Ball Club, have furnished a house and gone in together, to bach. They have a cook, to do their main work, and, besides living as well, will live more cheaply than at the hotel. One object of the boys is to establish a sort of Club room, or pleasant place where the members and their friends can spend the long winter evenings in ways of social benefit.[38]

The city may have fallen in love with its baseball team, but the players still had lives to live. Chase left the team after the Fourth of July match to go back east and attend Cornell University. Meanwhile, Crawford, still nursing a sprained ankle, suffered another injury when he sprained his arm “amusing himself in front of the Occidental,” prompting the newspaper to write with the sort of outsized despair the city’s baseball fans would embrace in the century to come, “the records of the Spanish Inquisition make no mention of the game of base-ball. The wheel and collar of spikes was good enough for those old fogies." [39]

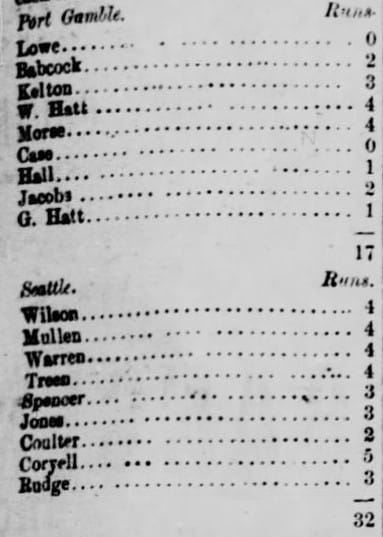

On August 11th, the Alkis took on a new opponent. The Unknowns of Port Gamble sailed into Seattle that morning. Their club was new, but the Alkis were down a few men, having lost Chase to college and Crawford to an arm injury. They were also without their regular second baseman, George D. Snow. Snow ran the telegraph office in town, the first in the city. He was needed in the office because telegraphs didn’t take the day off for baseball.

Players from the Second Nine filled in for the Alkis and played as well as the First Nine. The Alkis were victors again, winning 32 to 17. Following the game, the two clubs “were entertained to a sumptuous and elegant supper” at the players’ bachelor house followed by a dance in Yesler’s Hall.[40]

The club was undefeated in its first four games, and the pride of the city. They decided to play for the $200 first-place prize in the base ball tournament at the Oregon State Fair. The team held a soiree to raise money for the entry fee and travel costs. Unfortunately, as happens, rainy weather prompted the tournament organizers to cancel.[41]

Thus ended the first season of competitive baseball in Seattle.

The Alkis reorganized in 1878, with most of the same players. The success of the previous year was not duplicated and the team lost both games it played, both against Victoria. The team reorganized as the Elliotts in 1879 and, again, lost most of the matches it played.

That’s how it goes in baseball. But if you’ve ever found yourself caught up in the magic of an exciting Mariners season, perhaps you can relate to how that first year of 1877 felt to fans in Seattle getting their first taste of exciting, competitive baseball.

Fun Facts

- Although the Alkis and Lone Stars played what is considered the first match game in Seattle, this isn’t precisely true. The first mention in the newspapers of a match game of base ball in Seattle was on March 31, 1877, between the Seattle Amateur Club and the Young Centennials. In perfect Seattle fashion the game only lasted five innings, when it “came to an unexpected termination by reason of a shower of rain." [42]

- The Newcastle team recovered from its loss to the Alkis, and beat them in 1879. Newcastle would continue to field baseball teams, later playing in various mining leagues. The city's baseball history gets a fun entry when Rutherford B. Hayes became the first US President to visit the West Coast, along with Civil War General William T. Sherman. Micheal J. Intlekofer of the Newcastle Historical Society wrote to me:

After they visited the mine entrance, General Sherman took a tour into the mine, while President Hayes attended a baseball game.

In early years, the Newcastle baseball field was located west of town on a site later used by a brick plant, and now occupied by residential buildings and called the Newcastle Commons. This is where Hayes would have watched the game. In later years, the baseball field was located in Redtown near the Ford Slope mine in Coal Creek.[43]

Sources & Notes

- Puget Sound Dispatch, July 11, 1872, 3.

- https://www.inquirer.com/phillies/womens-baseball-philly-dolly-vardens-20240217.html

- Washington Standard, July 20, 1872, 2.

- BASE BALL. The Seattle Reds Preparing for Work, Seattle Daily Post Intelligencer, April 3, 1887, 8.

- The newspaper appears to have spelled the club name “Skooknni”, but other researchers have referred to it as Skookani. Either way, it’s likely derived from the Chinnok Jargon word “skookum”, which means strong, great, brave, and is used in many place names throughout Cascadia.

- Puget Sound Dispatch, May 1, 1873, 1.

- Post-Intelligencer, January 1, 1877, 3.

- Newcastle Historical Society, The Coals of Newcastle: A Hundred Years of Hidden History, 2020 edition, November 26, 2020, 14.

- Coals of Newcastle, 16.

- Coals of Newcastle, 30.

- A Trip to Newcastle, Post-Intelligencer, November 17, 1876, 3.

- Post-Intelligencer, October 10, 1878, 3.

- Weekly Pacific Tribune, June 30, 1876, 3.

- The Base-Ball Contest, Post-Intelligencer, August 23, 1876, 2.

- The Base-Ball Contest, Post-Intelligencer, August 23, 1876, 2.

- There seems to be debate to this day over how big a role he played, exactly. There is no smoking gun, but there is plenty of smoke. https://www.historylink.org/file/2746

- Baxter, Portus. "Pioneer Baseball in Seattle." Seattle Post-Intelligencer, October 24, 1909, Sporting Section, 3.

- Post-Intelligencer, March 21, 1877, 3.

- Post-Intelligencer, April 28, 1877, 2.

- Post-Intelligencer, April 30, 1877, 2.

- Post-Intelligencer, May 3, 1877, 3.

- Post-Intelligencer, May 7, 1877, 3.

- Post-Intelligencer, May 7, 1877, 3.

- Post-Intelligencer, May 7, 1877, 3.

- Strachan, Margaret Pitcarin, "Seattle's First Baseball Games." Seattle Times, September 7, 1947, Pacific Parade Magazine, 3.

- Post-Intelligencer, May 7, 1877, 3.

- "The Base Ball Game." Weekly Pacific Tribune, May 25, 1877, 3.

- "The Base Ball Game." Weekly Pacific Tribune, May 25, 1877, 3.

- Post-Intelligencer, May 25, 1877, 3.

- "The Victoria Excursion." Washington Standard, June 2, 1877, 4.

- Post-Intelligencer, May 25, 1877, 3.

- Post Intelligencer, June 6, 1877, 3.

- Post-Intelligencer, June 14, 3.

- Post-Intelligencer, July 6, 1877, 3.

- Post-Intelligencer, July 4, 1877, 3.

- Post-Intelligencer, July 7, 1877, 3.

- Post-Intelligencer, July 6, 1877, 3.

- Weekly Pacific Tribune, August 3, 1877, 3.

- Post-Intelligencer, August 3, 1877, 3.

- Weekly Pacific Tribune, August 17, 1877, 4.

- Post-Intelligencer, October 5, 1877, 3.

- Puget Sound Dispatch, March 31, 1877, 1.

- Email from Michael J. Intelkofer, January 20, 2026.

Comments ()