A Tale of Two October 2nds: The Pilots, the Mariners, and the Fate of Seattle Baseball

October 2, 1969 and October 2, 1995 were symbolic days for major league baseball in Seattle. A win, a loss, an end, a beginning, but only one answer for the question of whether Seattle was a major league city.

“What’s a Mariner?” Georg N. Meyers, sports editor of the Seattle Times asked in his column when the name for Seattle’s new baseball team was announced in 1976. “A Pilot, that’s what it is,” he answered.

“Pilots? We had that, didn’t we?”1

We did have the Pilots. And then we did not have the Pilots.

Now, after a lawsuit and a new ownership group and a shiny new domed stadium, we had the Mariners.

And not 20 years later the Mariners were talking about leaving town too. But the stars aligned and the team had a fateful run in 1995, hoping that this wasn’t 1969 all over again.

They ended the regular season tied for the lead in the American League West. The division title, a playoff berth, and, perhaps, their very existence in Seattle was on the line.

They played a one-game playoff to determine the division winner on October 2nd, the same day the Pilots played their final game.

As the two games unfolded across time, the fates of the Mariners and the Pilots were intertwined. They had many of the same challenges and the Mariners faced down issues that hadn’t been resolved with the Pilots.

History doesn’t repeat, but sometimes it rhymes.

The First Inning

The second day of October had the sort of weather that rolls into Seattle this time of year and announces that baseball season is over and fall is here. Light rain, mist, damp, chill as the sun went down, in both 1969 and 1995.

Though the weather was more suited for huddling on the bleachers at Husky Stadium on the other side of town, fans trudged out to the Rainier Valley on the evening of October 2, 1969. They were there to watch the final game of the Pilots’ inaugural season against the Oakland Athletics.

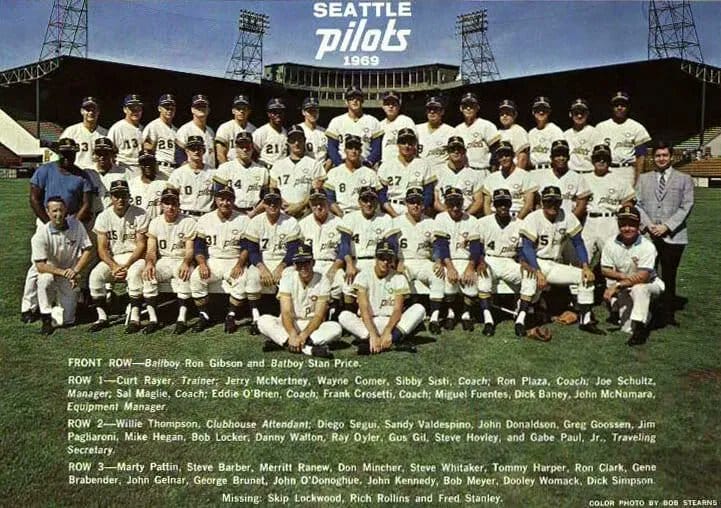

The sun had set and an autumnal chill settled over the outdoor stadium when Steve Barber threw his first pitch at 8 o’clock. He got two quick outs, then the Athletics loaded the bases. But, Barber came back and struck out Rick Monday to end the threat.

If only the other troubles that plagued the Pilots could be dispatched so easily.

* * * * *

The Pilots had a lot of problems, but it all came down to one major problem: They were broke as a joke.

The week before their final game, American League president Joe Cronin and William Daley, the majority stockholder of the Pilots, had a meeting with Seattle mayor Floyd Miller. The city wanted a letter of credit and performance bond for the continued use of Sicks’ Stadium. The team simply could not give that to them; they had no money, no credit, no trust from any of the institutions that could have helped them.

When the Mariners came to be, everyone was eager to avoid the Pilots’ financial issues. The members of the initial ownership group were vetted more carefully, but even they found the obligations of major league baseball were more than they’d bargained for. The Mariners were taken over for most of the 1980s by California businessman George Argyros, who also complained about the cost of the the team, then sold to media mogul Jeff Smulyan. Smulyan was also loathe to invest in the team and found himself in deep financial trouble as well.

The next ownership group that came in was Nintendo. The company’s American headquarters were local to Seattle, in Redmond. Although Nintendo’s Japanese CEO, Hiroshi Yamauchi, had no interest in baseball, he agreed to purchase the largest stake in the team.2

It was hard to be much more financially secure than being owned by Nintendo in the 1990s. Still, ownership was careful with their investment, unwilling to dump unlimited money into a small market team. But slowly, they began to build a team with a solid core.

For the first time in Seattle major league history, they were acting like a real baseball team.

* * * * *

The same damp weather on October 2, 1995 had no affect on the jubilation Mariners fans felt as they left the dreary weather outside and filled the Kingdome to the brim that afternoon.

It was the last game of the regular season, a one-game playoff against the California Angels to decide who would get to face the New York Yankees in the first round the playoffs.

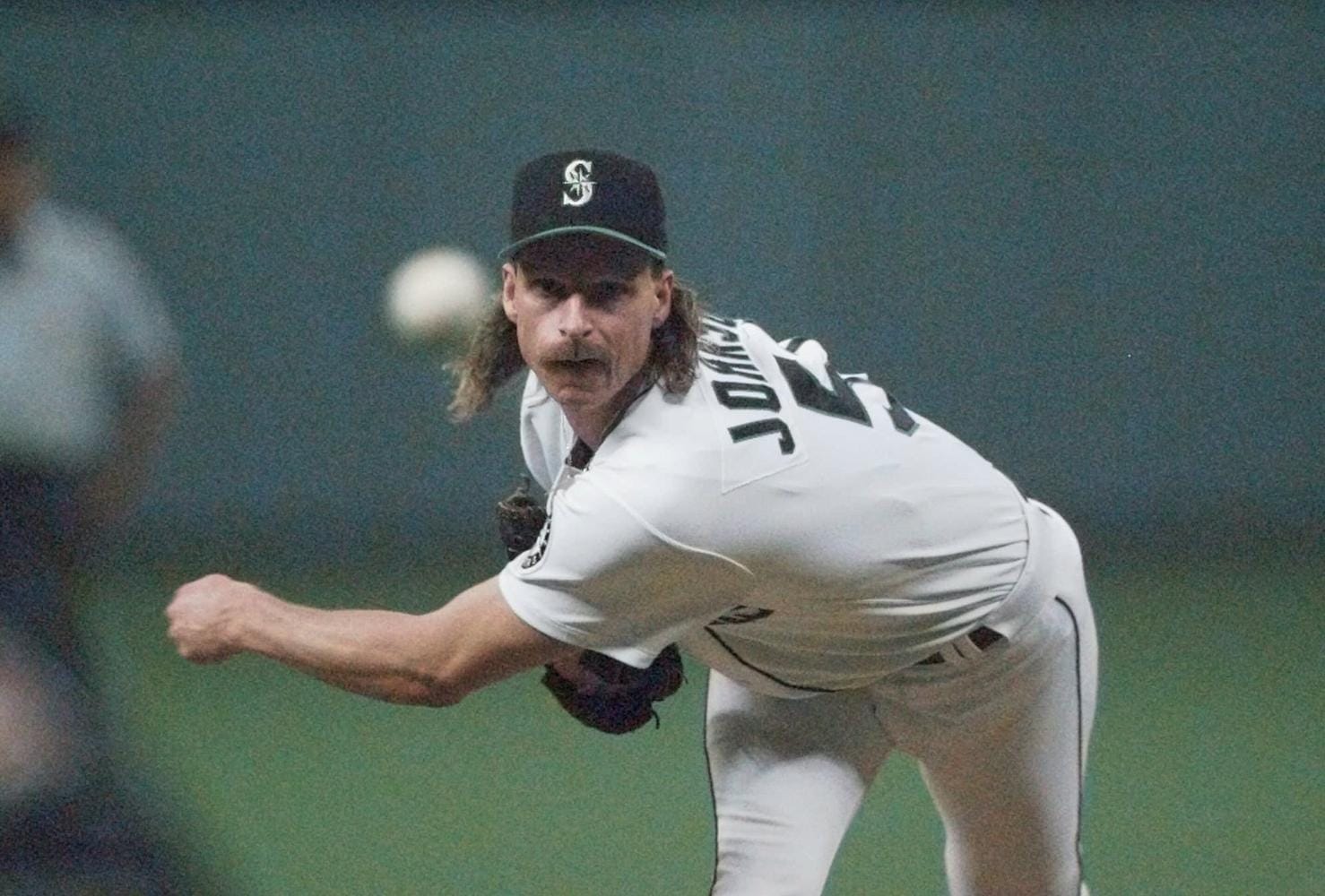

Randy Johnson was on the mound that day for the Mariners. He’d win the Cy Young Award. He was an All-Star. He was their Ace of aces, an 18-game winner who led the major leagues in strikeouts. He drove fear deep into the heart of every batter who faced him, particularly those unlucky lefties.

He only needed 10 pitches to shut down the top of the Angels order.

In the bottom of the inning, the Mariners faced Mark Langston, the pitcher they had traded to Montreal to acquire Randy Johnson in 1989. The matchup was a referendum on the moves the team had made beginning at the end of the 80s that brought them to 1995.

Vince Coleman led off with a single. Luis Sojo sacrificed him to second to put him in scoring position. With Ken Griffey Jr at the plate, Coleman tried to inch closer to home and was thrown out at third. Griffey drew a walk. Edgar Martinez followed with a single. Then, Jay Buhner grounded out to end the inning.

* * * * *

The Pilots went down 1-2-3 in the bottom of their first inning.

The Second Inning

Again with two outs, the Athletics got to Barber. This time, it was a couple of singles and Barber got out of it again.

In the bottom of the inning, once again, the Pilots went down 1-2-3.

* * * * *

The players on the 1969 Pilots had no control over anything that was happened to the team. They heard the rumors, they knew the situation. There was nothing they could do.

Mariners players also heard the rumors and knew the situation the team was in. They also couldn’t control anything off the field. But on the field, they had a collection of incredible individual players and as a group, they had enough talent to win. They were driven by the quest for personal baseball glory that every player wants, and they were driven to win for pride, for the city, for the fans who caught Mariners Fever and began to fill the Kingdome every night.

Now, in a one-game playoff, it was all on them. They could lose and the magic was over. They could win and keep it going. It was entirely up to them.

* * * * *

In the top of the second, Randy plowed through the middle of the Angels order again, easy as 1-2-3.

In the bottom of the inning, Mike Blowers drew a leadoff walk. But it was followed by a Tino Martinez popup and Dan Wilson hit into a double play. The Mariners were trying to threaten, but Langston was fighting them off.

Third Inning

Barber’s flirtation with trouble in the first two innings became serious in the third. The Athletics scored three runs before an out was recorded. Midway through, after the first two runs scored, Barber was replaced with John Gelnar. Gelnar surrendered one of Barber’s base runners on an RBI groundout, but got the next two batters to end it.

With one out in the bottom of the third, Pilots shortstop Ray Oyler hit a one-out single. Normally, a single would be fairly unremarkable, but a hit was never unremarkable for Ray Oyler. In fact, it was only his 42 hit of the season over 106 games.

Oyler was a sort of Mario Mendoza before Mendoza had seen a single professional pitch. Oyler finished the 1969 season with a batting average of .165, an improvement over his 1968 mark of .135. The Pilots took him as their third pick in the expansion draft, and Oyler became the most popular Pilot thanks to Bob Hardwick, a disc jockey at Seattle’s KVI 570 AM. KVI was evolving into a full service, middle of the road station and became the flagship for the Pilots. Hardwick was drawn to Oyler with his low batting average and formed the Ray Oyler Fan Club.

The Fan Club eventually boasted over 10,000 members. Hardwick officially called his club the “Soc It To Me .300 Club.” It was a play on the catchphrase from a popular television show at the time, “Rowan and Martin’s Laugh In.”3 It stood for “Slugger Oyler Can, In Time, Top Our Manger’s Estimate” and encouraged fans to believe that Oyler could hit .300.

He never did, of course, but as he was embraced by the fan club he fell in love with Seattle. Even when the Pilots, he stayed and made it his home.

Before the game, a member of his fan club presented him with a “large elaborate cake with the names of all the players on it.”4

The 1995 Mariners were stacked with real stars like Randy, Ken Griffey Jr., and Edgar Martinez, and full to the brim with players that everyone is delighted to remember.

There was Joey Cora, who firmly establish himself in Seattle hearts when he sobbed in the dugout after the Mariners were eliminated from the 1995 ALCS. There was Dan Wilson. There was the duo of Edgar and Tino Martinez, Double Martinez Time. There was Mike Blowers and his Blowers Power. There was Alex Diaz and Greg Pirkl, and Luis Sojo, the role players who were loved by Seattle fans far beyond their on-field contributions.

A winning baseball team is great, but the real connection for fans to their baseball team is always the players.

* * * * *

Pinch hitter Gus Gil grounded into a double play that snared Oyler at second. No score for the Pilots

* * * * *

Randy Johnson strikes out the side in the top of the third. In the bottom, Luis Sojo offers a two-out single. But he is stranded.

Fourth Inning

Dick Baney takes over on the mound for the Pilots and for the first time, the Athletics go down 1-2-3.

* * * * *

The face of the Pilots ownership were the brothers Max and Dewey Soriano. Dewey was the president of the Pacific Coast League when he was encouraged by American League president Joe Cronin to pursue a major league team in Seattle. He had been the general manager of the Seattle Rainiers, the longtime popular Pacific Coast League team in Seattle. Both Soriano brothers were embedded in the local baseball community and seemed like an obvious ownership choice if no one looked much further.

The Sorianos may have been tight with baseball, but they were not part of the broader financial community in Seattle. They had trouble approaching companies and businessmen to ask for investments when they’d never interacted with them before. They were so far outside the business scene, no one inside took them seriously and the Pilots were viewed locally as a bad investment.

As the financial troubles mounted, the Sorianos brought in William Daley to take over as the majority stakeholder. Daley was a former owner of the Cleveland Indians, and was familiar with Seattle; he had considered moving the Indians from Cleveland to Seattle. Though Daley may have had more experience running a team, he was halfway across the country with no real connections to Seattle.

Likewise, the Mariners often felt the effects of an absentee owners. Though Nintendo’s offices were local, the owner was in Japan. In fact, he never saw the Mariners play a single game. He’d bought the team out of a sense of civic duty, but had little interest beyond that. And after a couple decades of losing, Mariners fans still hadn’t bought into the team. Too much losing, too little promise of anything ever changing.

* * * * *

Stop me if you’ve read this before. In the top of the inning the Angels went down 1-2-3.

Edgar led off the bottom half with a single, but still no score when he was followed with a strikeout and a double play.

Fifth Inning

Facing Dick Baney, Tommie Reynolds singles with two outs in the top of the fifth. He is caught stealing to end the inning.

In the bottom of the fifth, the Pilots get another hit! It’s a two-out bunt single from Steve Hovley. But no runs score when Ron Clark pops out to end the inning.

* * * * *

The Pilots were supposed to play their first season in 1971, the time line set in 1967 when Charles Finley won approval to move the Kansas City Athletics west to Oakland. Kansas City Mayor Ilus Davis threatened to file a lawsuit to block the move and Missouri Senator Stuart Symington threatened to challenge Major League Baseball’s antitrust exemption and reserve clause if Kansas City did not have their team replaced right away. The American League opted to avoid those legal entanglements by moving the expansion time line up to 1969 and giving Kansas City a new team that year.

Along with the Kansas City Royals came the Seattle Pilots. The accelerated time line exacerbated all the financial issues the Sorianos would have. The American League was eager to snag the growing Seattle market before the National League got there, and they wanted to avoid trouble in Kansas City. So although they probably should have known better, the Sorianos were awarded the team and the Pilots were born in 1969.

The Mariners, on the other hand, were born out of a lawsuit King County filed against the American League when the Pilots relocated to Milwaukee. Seattle was awarded a team in Feburary 1976 that would begin playing the following year. But people in Seattle were a little skeptical this team would work out any better.

As Georg N. Meyers continued in his column about the nicknamed Mariners, “What will be the team’s mascot? The albatross? What will be the team’s emblem? A life preserver? An anchor? A dramamine pill?”5

An albatross may well be the most accurate mascot the team could have chosen.

* * * * *

Randy Johnson, once again, strikes out the side of Angels. He is perfect through five innings.

In the bottom of the fifth, Tino Martinez draws a leadoff walk, but is forced out at second on a Dan Wilson bunt. Joey Cora follows with a single and Vince Coleman drives in Wilson with a single and the first run of the game. Then Luis Sojo hits into a double play. But the Mariners finally got to Langston for a run.

Sixth Inning

Phil Roof hits a one-out single for the Athletics, but he’s stranded. In the bottom of the sixth, the Pilots go down 1-2-3.

* * * * *

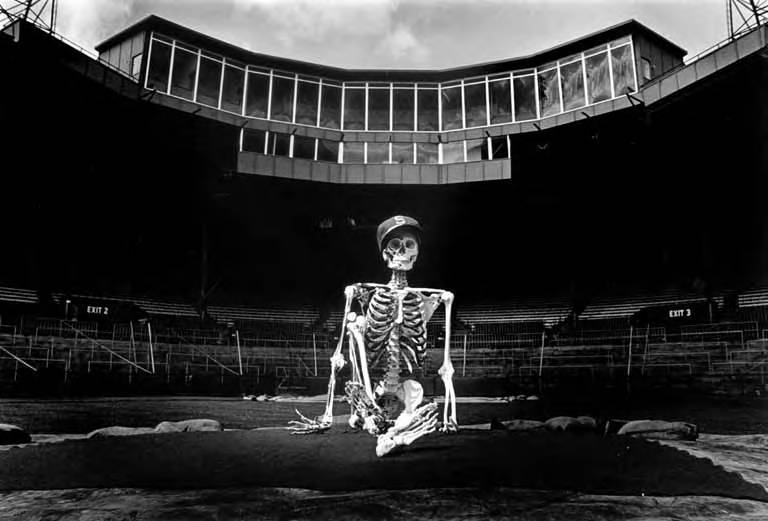

Sicks’ Stadium had once been a crown jewel in Seattle and in minor league baseball. Built by Rainier Brewing Company magnate Emil Sick in 1938, it was home to the minor league Seattle Rainiers until 1964. The team became the Seattle Angels for a few years until the Pilots moved in.

The city of Seattle bought the stadium in 1965, anticipating that they would tear it down and build a freeway. As such, they did very little maintenance. Civic leaders believed they had time to build a new domed stadium before major league baseball came to Seattle. However, when the Pilots began in 1969 Sicks’ Stadium was the only option.

Pilots ownership and the city of Seattle scrambled to upgrade the stadium to vaguely major league standards. But even after costly renovations and cost overruns, the stadium was a dump. In 1968, King County voters passed an initiative to fund a multipurpose domed stadium. If the Pilots could just hang on a little longer, they’d have a new stadium.

That domed stadium, the futuristic Kingdome opened in 1976. Rather than being a savior, it was beset with problems from the beginning. The roof leaked, it was dark, it was shared with every other Seattle team. When the original ownership group gave way to Argyros in 1981, Seattle fans began to hear the first threats to move the team unless the stadium was fully renovated or replaced. Smulyan echoed Arygyros’s complaints.

By the summer of 1993, the Nintendo ownership group also come to the conclusion that they needed a new baseball stadium, or the team would need to leave town. Naturally, after nearly two decades of terrible teams on the field, voters weren’t inclined to publicly finance a stadium. The state legislature rejected the use of state taxes for a stadium and the issue went on the ballot in King County. As the Mariners made a run at winning the division, a vote was held on September 19th.

The measure narrowly failed; in fact, the vote was so close that it’s widely assumed that had the vote been held a week later, with the run the Mariners were on, it would have passed. But it failed and ownership set a deadline of October 30th for the state and county to fund a new stadium.

* * * * *

With two outs, Rex Hudler gets the first Angels hit of the day, then rubs it in by stealing second base. But Randy strikes out Tony Phillips and puts a stop to that nonsense.

Seventh Inning

Ray Oyler left the game after the sixth inning when Bob Locker came in to pitch. Locker induced three easy ground outs from the Athletics.

The A’s starter, Jim Roland, was still rolling in the seventh, sending the Pilots back to the dugout in order.

* * * * *

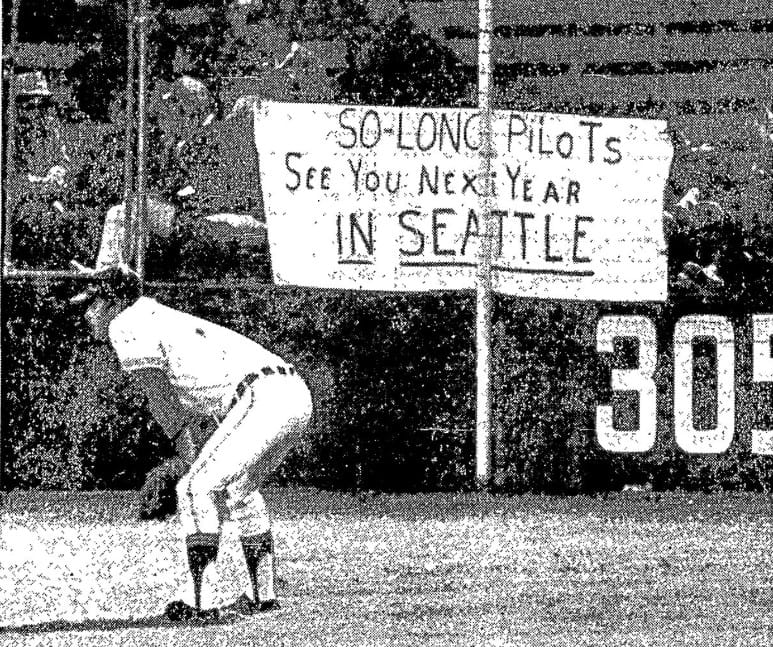

Rumors that the Pilots might leave Seattle were as thick as the mist in the early October air. William Daley himself told newspapers that he’d had interest from businessmen in Texas who wanted to move the Pilots to Dallas-Fort Worth. There were rumors that Milwaukee was interested, having lost the Braves after 1965. Three major league teams had relocated in the 1960s alone. It wasn’t hard to see that the Pilots were likely next.

After the meeting a week before the end of the season with Joe Cronin and Seattle Mayor Miller, Daley told reporters, “Seattle has one more year to prove itself.” This was met with a sea of anger from newspaper columnists and fans. In a letter to the Seattle Times editor, David S. Johnstone of Kent wrote, “I feel Daley needs to be reminded of several points, among them that the Pilots have the highest admission prices in the American League and are the worst team in the American League.”6

Georg N. Meyers scoffed of Daley’s threat, “That’s upside-down, isn’t it? What we’re really doing is giving Daley one more chance.”7 And Hy Zimmerman of the Times bristled at the insult to Seattle fans, “The area’s baseball fans, considering the circumstances in which they watched the Pilots, at no small outlay, deserve a salute, not a slap.”8

There was no “one more year.” The Pilots opened the 1970 season in Milwaukee.

As soon as they left, Seattle filed a lawsuit asking the American League to place a new team in Seattle, alleging it had broken its contract with the city when it allowed the Pilots to relocate.

But it took less than a decade for fans and city of Seattle to have the relocation threat hung over their heads again. Now, after the popular vote for stadium funding failed, the team threatened, fund a new stadium by October 30, or else.

Seattle was on the verge of losing its second major league team.

* * * * *

His perfect game may have been gone, but Randy was still Randy. Again, in the top of the seventh, only three Angels came to the plate.

Langston was on his third trip through the Mariners order, reaching the bottom of the order in the bottom of the seventh. Mike Blowers led off with a single, then Tino laid down a sacrifice bunt to advance Blowers to third base, but both he and Tino were safe. Dan Wilson followed with a bunt that moved them both into scoring position. Joey Cora was up next, and Langston hit him with a pitch. Vince Coleman lined out to short right field and Blowers was unable to score.

The bases were loaded. There were two outs. Luis Sojo stepped up to the plate. This was the sort of moment where time slowed down. This was the most potent threat the Mariners had launched against Langston. It felt like this was do or die. Drive in some runs. Give Randy some room. Keep baseball going in Seattle.

No pressure.

Sojo hit a broken-bat ground ball down the first base line. It bounced into the Angel’s vising bullpen in foul territory and rattled around under the bullpen bench.

Blowers and Tino came in to score with Cora and Sojo racing around the bases behind them. Langston cut off the throw and threw it over his catcher, Andy Allanson. Joey scored. Allanson retrieved the ball and threw it toward Langston covering the plate.

Sojo slid hard and fast across the plate to score. All Langston could do was collapse on the ground in disbelief.

Eighth Inning

Locker continued his good relief in the eighth, only facing three Oakland batters. On the Pilot’s side, it looked like they were cooking something up with a leadoff double from Jerry McNertney and another bunt single from Steve Hovely. Unfortunetely, they couldn’t get a run across the plate.

* * * * *

Attendance was poor at Sicks’ Stadium in 1969. It was a dump. It was expensive. The Pilots were…not good. Sure, they were an expansion team. What do you expect? But attendance was a big part of teams’ financial strength in 1969. The Pilots hoped for a million in attendance, and needed a little less to break even. They wound up sitting at 678,000.

On the final game of the first season, only 5,473 fans entered the gates to see them play.

In contrast, over 52,000 fans filled the Kingdome. But this boost in attendance was new, fueled by the team’s run for the division title. It was the end of 19 long season of frustration, of futility, of boring, boring baseball. Suddenly the baseball was fun and exciting.

It was everything Seattle baseball fans had been waiting for since the first discussion of a major league team in Seattle.

For all the talk of needing to build a good ballpark to make the fans come out, it turns out, all they needed was good baseball.

* * * * *

Chili Davis drew a leadoff walk and Rene Gonzales hit a two-out ground rule double, but Randy barely sweat as he extinguished the threat.

The Mariners scored four more runs in the bottom of the eighth. They led 9-0 with but an inning left to play.

Ninth Inning

Miguel Fuentes came into the game for the Pilots. Despite a couple base runners, he got out of it and the Athletics went into the bottom of the ninth, ahead 3-0.

Tommy Harper led off with a single for the Pilots, and went for his 74 stolen base, which would tie Lou Brock’s mark for the second-highest total in baseball since Ty Cobb. But like the Pilots as a whole, he went for it and missed, caught for the first out.

Steve Whitaker followed with a solo home run to deep right field. It was his sixth of the season, but his second in two nights. After Wayne Comer flew out, Greg Goossen singled. Then catcher Jerry McNertney came to plate and struck out.

And that was all the Pilots wrote, losing their final game 3-1.

One of the reasons the American League was eager to stake a claim in Seattle in the 1960s was because Seattle loved its Rainiers. The Rainiers were a minor league team that played under that name on and off from 1919-1968. The glory days of the franchise began when Emil Sick took over the team in 1938 and built Sick’s Stadium. The team drew well, and regularly won Pacific Coast League pennants.

The Pilots should have been the worthy heirs of that baseball tradition. But, at a time when Seattle was trying to turn itself into a major city and fighting the reluctance of Seattlites to do so, maybe Seattle just wasn’t a major league city?

Fans were skeptical again when the Mariners showed up. They’d already been hurt. And again, the Mariners repeated the mistakes of the Pilots, blaming the fans for not supporting teams that ownership refused to support themselves.

And then, at the first hint that the team cared, that the players cared, the Kingdome was full. It wasn’t just the winning, it wasn’t just the stretch run. It was that suddenly every part of the team seemed to care as much as the fans wanted to care.

The Kingdome in September and October 1995 was unlike any other baseball experience. It was louder than football games. It was over 50,000 people who lived and died with every pitch. Who stood up and screamed and cheered and poured their souls into every two-out, two-strike pitch.

There were Mariners hats and t-shirts on every street, people talking about the Mariners with strangers, a feeling of civic togetherness that hadn’t existed since the Rainiers.

Because as silly as it sounds, fans just want to be part of the team. And in 1995, the Mariners let us all join.

* * * * *

In the top of the ninth inning, Tony Phillips led off with a home run, but it didn’t matter. Spike Owen flew out and Eduardo Pérez grounded out. Then Tim Salmon came to plate and struck out.

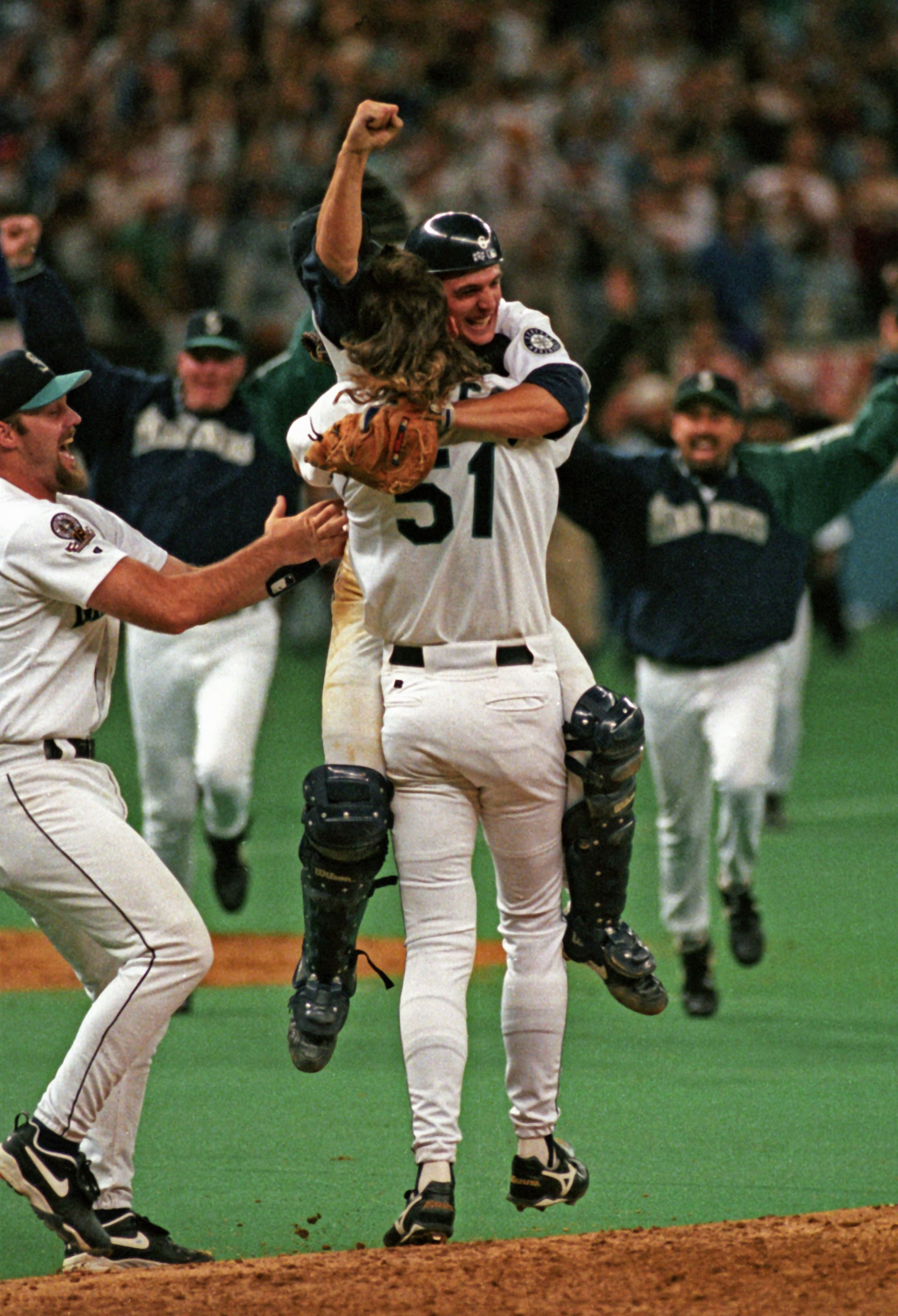

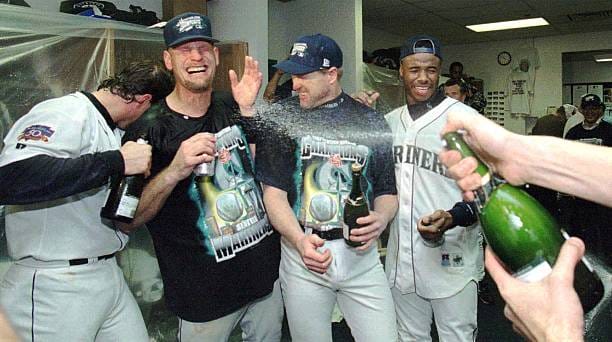

The Kingdome erupted. Randy pointed to the sky as he was rushed by teammates. Fans streamed over the walls onto the field.

It was a celebration like nothing before in Seattle baseball.

The Mariners won the division. The Mariners were a playoff team. They would get their new stadium and major league baseball was finally secure.

The Mariners had undeniably made Seattle a major league baseball town.

Notes:

- Georg N. Meyers, "Seattle Mariners? Glub! Glub!" Seattle Times, August 25, 1976: 24.

- https://uproxx.com/sports/seattle-mariners-nintendo-ownership/

- It was also a line in Aretha Franklin’s Respect, which was released in 1967. The TV show is credited with the Soc(k) It To Me tag line; an actress from the show is referenced on the membership cards. But it’s makes more sense for it to be a reference to the song Respect if you ask me!

- Lenny Anderson, "Pilots End It With Loss." Seattle Post-Intelligencer, October 3, 1969: 55.

- Georg N. Meyers, "Seattle Mariners? Glub! Glub!" Seattle Times, August 25, 1976: 24.

- "Times Readers have Their Say." Seattle Times, October 1, 1969: 12.

- Georg N. Meyers, "Just One More Chance: The Daley Ultimatum. " Seattle Times, September 29, 1969: 21.

- Hy Zimmerman, " Won't You Go Home, Bill Daley?" Seattle Times, October 2, 1969: 45.

Comments ()